The memory usually arrives without warning. You’re reaching for the salt at dinner and suddenly you’re eight years old again, sitting cross‑legged on the shag carpet, watching the moon landing on a bulky TV that clicks when you change channels. Or you can still smell the plastic of your first Walkman, hear the clunk of the cassette door, feel the careful rewind with a pencil. These aren’t just cute stories to bore the grandkids with. They’re crystal‑clear, high‑definition scenes from decades ago that somehow live right under your skin.

10 moments from decades ago that your brain remembers for a reason

Ask people in their 60s, 70s, even 80s what they remember, and they don’t talk about last Tuesday’s lunch. They jump straight to the Technicolor scenes. The day the teacher rolled a TV into the classroom to watch the Challenger launch. The exact spot in the supermarket where they heard Elvis had died. The burn of the sun on their arms the first time they drove a car alone. These memories arrive fully furnished: the weather, the outfits, the song on the radio.

That vividness isn’t random nostalgia. It’s how the brain files the moments that mattered. Not on a dusty shelf, but in a glass case.

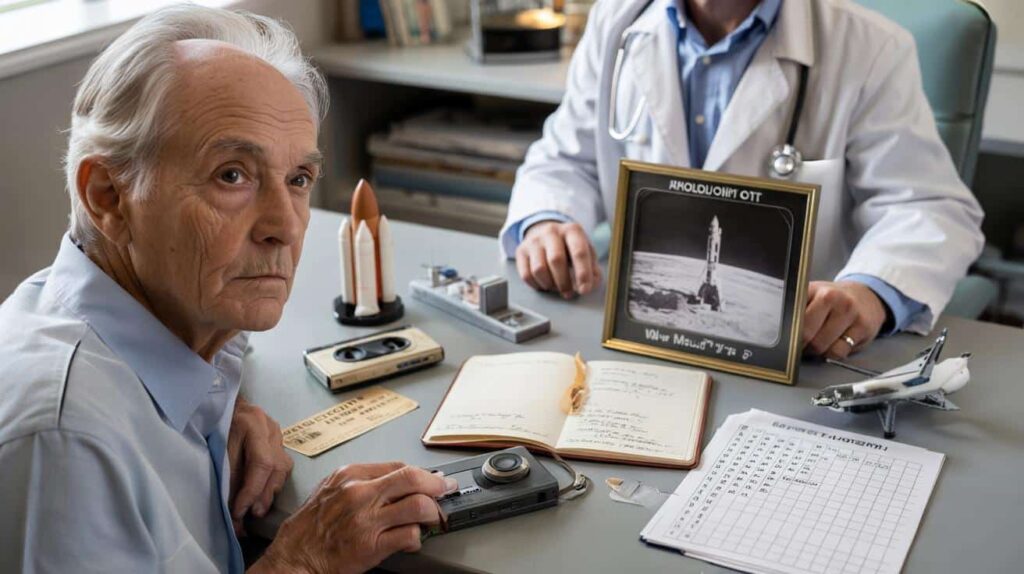

One neurologist I spoke to told me about a patient in her late seventies, flagged by a routine screening as “possibly cognitively impaired.” She couldn’t recall three simple words after five minutes, the kind of test many clinics still use. But when the doctor casually asked what she remembered from 1969, the woman’s eyes lit up. She described the Apollo 11 landing as if she were commentating live. The crackle of the black‑and‑white set. Her father yelling for the neighbors. The way the whole street went suddenly quiet.

She described the precise path she walked to school that year. She remembered the color of her bag and even how the chalk dust smelled in her classroom. The test results indicated a problem. But her detailed memories showed that her brain was still building connections at a rapid pace.

There is a reason many people remember certain moments from the past more clearly than what they bought at the store yesterday. Psychologists have a name for this phenomenon called the reminiscence bump. This describes how our brains store memories from our teenage years and early twenties with unusual strength. These years contain many first experiences. Your first romantic relationship. Your first real job. The first election night you stayed awake to follow the results. When strong emotions combine with new experiences the brain creates lasting memories. This explains why some people can still remember every detail of the day John Lennon died or recall the exact smell of newspaper ink when they read about the Berlin Wall coming down. These vivid recollections reveal something important about how memory systems develop during those formative years.

The trap is simple. Many screening tools rely too much on short tasks that lack context. They ask patients to repeat a list or draw a shape or name some animals. When doctors use only these measures a normal age-related memory slip can appear to be early dementia. This problem gets worse when the doctor has just ten minutes and a waiting room packed with people waiting to be seen. The issue becomes more complicated because these brief tests cannot capture the full picture of how someone functions in daily life. A person might struggle to remember three words in a clinical setting but still manage their finances and maintain their independence at home. The artificial nature of the testing environment can create anxiety that affects performance. Someone who feels nervous or rushed may perform worse than they would in a familiar setting. Doctors often face pressure to make quick assessments. Insurance companies and healthcare systems push for efficiency. This means less time for thorough evaluation and more reliance on standardized screening tools. The tools themselves were designed to flag potential problems but they were never meant to serve as definitive diagnostic instruments. They work best as a starting point for further investigation rather than as a final answer. The consequences of misdiagnosis can be significant. A false positive result can cause unnecessary worry and lead to expensive follow-up tests. It might prompt families to make premature decisions about living arrangements or financial matters. The psychological impact on the patient can include depression and loss of confidence. Some people begin to doubt their own abilities and withdraw from activities they previously enjoyed.

When sharp old memories clash with quick dementia tests

One practical thing experts are quietly starting to do is build the long life you’ve already lived into the assessment. Not just “Who is the president?” but “Where were you when the Berlin Wall fell?” Not just “Memorize these five words” but “Tell me about your first car, your first big news story, your first concert.” These aren’t cozy small talk. They’re high‑value brain checks. If you can navigate those moments in detail, sequence them, and connect them with dates or phases of your life, your brain is showing off skills that a two‑minute test simply doesn’t catch.

➡️ A young mother lends her savings to her unemployed brother, but her husband calls it betrayal: “You’re stealing from our children” – a moral dilemma that divides opinion

➡️ How to keep mice seeking shelter out of your home: the smell they hate that makes them run away

➡️ Goodbye induction hobs in 2026, as experts predict a new kitchen technology could soon replace them in many homes

➡️ At 2,670 meters below the surface, the military makes a record?breaking discovery that will reshape archaeology

➡️ The return of the aircraft carrier Truman, a signal badly received by the US Navy facing future wars

➡️ Doctors under fire as they warn seniors with joint pain to avoid swimming and Pilates and choose this unexpected activity instead

➡️ Bad news for homeowners: starting February 15, a new rule bans lawn mowing between noon and 4 p.m., with fines at stake

➡️ Almost nobody knows this, but placing aluminum foil behind radiators can noticeably lower heating bills

Think of it as something other than trivia. It works more like a guided tour through your mental storage system. This process takes you through the information you have collected over time. Your brain holds countless memories and facts in an organized way. When you explore these stored pieces of knowledge, you are not just recalling random details. You are walking through a structured collection of everything you have learned and experienced. The tour moves through different sections of your memory. Each area contains specific types of information. Some parts hold facts you learned in school. Other sections store personal experiences and moments from your life. There are also spaces filled with skills you have developed and patterns you have recognized. As you move through this mental archive connections appear between different pieces of information. One memory links to another. A fact you learned years ago suddenly relates to something you discovered recently. These connections help you understand how your knowledge fits together. The guided aspect means you follow a path through this information. Rather than jumping randomly from one thought to another, you take a deliberate route. This approach helps you see how ideas build on each other. You notice themes and patterns you might have missed before. Your neural archive is always growing. Every day adds new information to the collection. Some additions are small details that fill in gaps. Others are major insights that change how you see entire sections of your stored knowledge. The tour reveals not just what you know but how you know it. You see the structure behind your understanding. You recognize which areas are well developed and which ones need more exploration. This awareness helps you learn more effectively in the future.

Here’s where many people start doubting themselves. They ace the “Do you remember where you were when Princess Diana died?” question, can describe the room, the channel, even the headlines the next day. But then they forget their PIN code or walk into the kitchen and blank on why. That gap feels terrifying. “I can remember the lyrics to every Beatles song, but not my neighbor’s name, so something must be terribly wrong.” We’ve all been there, that moment when a simple lapse suddenly feels like a diagnosis.

This is the crack where fear, rushed appointments, and oversimplified tests fall in together. A normal, stressed, distracted brain can look just like a sick one if you only test it in narrow, artificial ways.

The plain truth is that a lot of frontline dementia screening still works like a metal detector at an airport: it goes off at anything. Medications, poor sleep, depression, hearing loss, grief, chronic pain, and plain old stress can all drag down short‑term recall. Yet if your long‑term, emotionally rich memories are intact, structured, and detailed, that’s a big clue that deeper brain networks are still functioning. *Confusing everyday forgetfulness with dementia risk isn’t just unhelpful, it can be dangerous.* People lose confidence, withdraw from activities, stop challenging their minds, and that retreat itself can accelerate real cognitive decline.

Your ability to remember those 10 (or 50) moments from decades ago is a quiet protest against one‑size‑fits‑all dementia labels.

How to talk to your doctor so your real memory gets seen

One practical step can shift the entire discussion. Before you meet with a doctor about memory concerns take time to write down ten clear memories from when you were younger. Include major historical events like Nixon’s resignation, Live Aid or the Y2K scare. Also write down personal moments such as your wedding song, your first apartment the birth of your first child or the train route to your first job. This simple exercise creates what some call a memory map. It gives you concrete examples to share during your appointment. When you bring specific memories to discuss, you help your doctor understand what you can remember clearly. This makes the conversation more productive than simply saying you have memory problems. The process of creating this list also helps you see patterns. You might notice that certain types of memories remain vivid while others have faded. Some people remember emotional events better than routine activities. Others recall visual details but struggle with names or dates. These patterns provide useful information for your healthcare provider. Writing down memories before your appointment serves another purpose. It reduces anxiety about forgetting things during the visit itself. Many people worry they will seem more confused than they actually are if they cannot think of examples on the spot. Having your list ready means you can focus on the conversation instead of searching your mind for examples. Your memory map does not need to follow any special format. A simple numbered list works fine. Just make sure each entry includes enough detail that you can explain it clearly. Instead of writing “my wedding” you might note “dancing to Unchained Melody at my wedding reception in 1990.” The extra details make each memory more useful for discussion. This preparation shows your doctor that you are taking an active role in understanding your memory. It demonstrates that you can still access long-term memories even if you have concerns about recent events. Most importantly, it transforms a potentially vague conversation into one grounded in real examples that both you and your doctor can examine together.

For each, jot two or three details you can still see, hear, or smell. That little exercise already shows you more about your brain than a waiting‑room questionnaire.

Then bring that list in. If you feel rushed, you can say something like, “I know I sometimes lose my keys, but I also have a lot of very clear older memories. Can we look at the whole picture?” That isn’t arguing with the doctor. It’s giving them more data. A good clinician will be relieved; it gives them a chance to distinguish between attention issues, normal aging, medication side effects, and real red flags. A not‑so‑good one may brush it off; that tells you something too.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day. Most of us only push back when a label starts to feel heavier than our actual life.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can say in a medical office is also the simplest. You might tell your doctor that a test result does not match how your life actually feels. Then you can ask if it makes sense to look deeper into what might be going on. This kind of honesty takes courage because test results often seem final. Doctors rely on numbers and data to make decisions. When lab work comes back normal it can feel like the conversation is over. But your daily experience matters just as much as any number on a page. Many people leave appointments feeling unheard when their symptoms are real but their tests look fine. They wonder if they imagined their problems or if they are overreacting. The truth is that standard tests do not catch everything. Some conditions take time to show up in bloodwork. Other health issues do not have clear markers that labs can measure. Speaking up about this gap between your results and your reality opens the door to better care. It tells your doctor that something still needs attention. A good physician will take this seriously and consider other possibilities. They might order different tests or refer you to a specialist who can investigate further. Your body sends you signals every day. You know when something feels wrong even if you cannot name it precisely. That knowledge deserves respect in any medical setting. Trusting yourself enough to voice that concern is an important part of getting the help you need.

- Write down 10 vivid memories from ages roughly 10–35, with at least two sensory details for each.

- Bring a list of your current medications, sleep habits, and mood changes; these often affect short‑term memory more than age does.

- Ask specifically whether long‑term autobiographical memory was considered, and if not, request a fuller cognitive assessment.

- Consider bringing a relative or friend who can describe what you remember well and what’s actually changed, beyond the odd name‑forgetting.

- If you feel dismissed, don’t be afraid to seek a second opinion from a neurologist or memory clinic with longer assessment slots.

The silent shift: from fear of forgetting to curiosity about what still works

Once you start paying attention, you may notice something surprising. Your mind might be less “going” and more “changing channels.” Names and calendar appointments slip through the cracks more easily, yes. But old scenes keep surfacing with a kind of stubborn clarity. The bus you took to school in 1974. The exact pattern on your grandmother’s tablecloth. The nervous excitement the night you stayed up to watch the first Gulf War unfold on CNN. These aren’t useless files. They’re proof that your brain still knows how to weave together time, emotion, and detail.

There’s a quiet power in refusing to let a ten‑minute screening test define that. When people start sharing these sharp old memories with family, something else shifts. Grandchildren hear living history instead of generic warnings about “grandma losing it.” Partners stop chalking every misplaced phone up to “early dementia” and start asking better questions about stress, sleep, or loneliness. And doctors, when they listen, can begin to see older patients less as walking risk charts and more as complex minds with long, still‑vivid stories. The medical system may be slow to catch up, but your own voice — and your own archive of remembered moments — can nudge it in a better direction.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| — | Sharp old memories often signal preserved brain networks, even when short‑term recall feels shaky. | Reduces unnecessary fear and encourages a more nuanced view of aging. |

| — | Quick dementia screens can over‑flag normal aging, stress, or medication effects as “cognitive impairment.” | Helps readers question oversimplified diagnoses and ask for fuller assessments. |

| — | Preparing a “memory map” and specific questions gives doctors better data and patients more control. | Empowers readers to advocate for themselves and avoid mislabeling. |

FAQ:

- Question 1Is being forgetful sometimes a sign that I’m definitely developing dementia?

- Question 2Why can I remember events from decades ago more clearly than what I did last week?

- Question 3Can dementia tests at my regular clinic really be wrong or misleading?

- Question 4What should I say to my doctor if a memory test worries me but doesn’t match how I feel?

- Question 5How can my family tell the difference between normal aging and something we should check out?