What lay inside, wrapped in silence and old instructions from a fallen dynasty, now forces historians, lawyers and descendants to rethink who truly owns the glittering remnants of an empire.

A suitcase that fled an empire

The story begins with the collapse of the Austro‑Hungarian Empire at the start of the twentieth century. As borders shifted and monarchies crumbled, the Habsburg family faced a blunt reality: survival mattered more than ceremony.

Empress Zita, widow of the last emperor Karl I, left behind palaces and official regalia. She chose instead a modest suitcase. Into it, she placed private jewels: pieces that were easy to hide, easy to carry and easy to sell if the family ever needed cash.

These were not just luxury items. Each jewel was a discreet savings account and a fragment of family memory, meant to travel where the imperial court no longer could.

Flight across a continent at war

The suitcase’s second dramatic journey came in 1940. With German troops advancing through Belgium, Zita and her children were forced into a hurried escape. They had only hours to leave.

The family crossed through Portugal, one of the last open doors in wartime Europe, then boarded a ship for Canada. They settled in Quebec, drawn by the French language and the promise of a quieter life.

In North America, their days bore little resemblance to court life in Vienna. Yet behind that modest appearance, Zita remained focused on safeguarding what was left of the Habsburg legacy.

A century-long secret in a Canadian bank

Shortly after arriving in Canada, Zita placed the suitcase inside a bank safe deposit box. She refused to reveal its contents, even to those closest to her.

Instead, she left a strict instruction: the box was not to be opened until one hundred years after the death of Emperor Karl, who died in 1922. That meant 2022 was the earliest possible opening date.

Across decades, Habsburg descendants quietly kept paying the rental fees. They did so without touching the lock, preserving a promise to a grandmother most of them barely remembered. The suitcase became a time capsule, untouched by wars, regime changes and family financial setbacks.

The Habsburgs did not lose every treasure to revolutions and auctions; some simply waited in silence for the right key.

What the heirs found inside

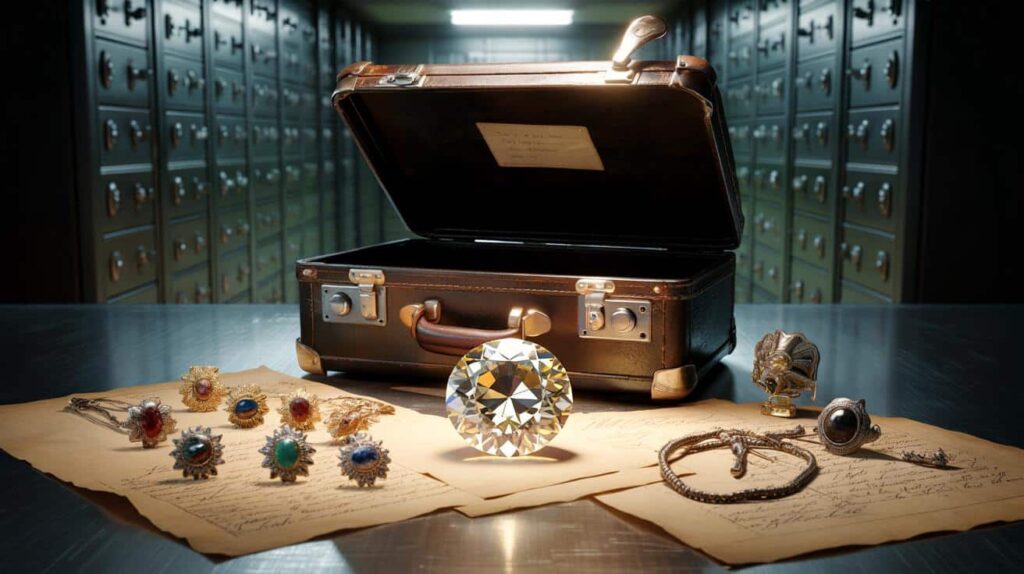

When the box was finally opened in a Canadian bank, the scene mixed suspense with almost theatrical precision. Inside, the old suitcase was intact. And inside the suitcase: gleaming jewels wrapped in layers of cloth, seemingly unchanged by a hundred years of sleep.

Among brooches, decorative badges and hairpins, one stone immediately stood out. It was a large, pale yellow diamond, cut in an old style that no modern jeweller would attempt lightly.

Experts called in to examine the stone noticed its unusual double rose cut, a shape associated with Renaissance workshops. Historical descriptions matched what they saw. Soon, the identification followed: this was almost certainly the legendary Florentine Diamond, long thought to have vanished from history.

The Florentine Diamond, back from the shadows

The Florentine Diamond has hovered somewhere between myth and fact for generations. Weighing close to 137 carats, the stone has been described as a light yellow gem with a complex star‑like pattern of facets.

It passed through several European ruling houses before entering the Habsburg collection. After the First World War and the fall of the monarchy, it disappeared from public records.

For a century, rumours circulated. Some insisted the stone had been stolen. Others claimed it had been secretly recut and sold. None of those stories could be confirmed.

The suitcase shows that the Florentine Diamond was not stolen or smuggled out in a private sale; it simply never left Habsburg hands.

Matching portraits and jewels

Historians assessing the Canadian find went beyond weight and colour. They compared each piece with old court portraits and photographs. Brooches and star‑shaped decorations appeared in official paintings of Habsburg ceremonies. Pins seen on uniforms in black‑and‑white images resurfaced in the suitcase, gem for gem.

This visual cross‑checking reinforced the conclusion: the collection was authentic, and the diamond matched historic descriptions of the Florentine. The pieces were not later imitations but original imperial jewels, frozen in time since the family’s flight.

Who owns a lost imperial diamond today?

The return of the Florentine Diamond raises uncomfortable questions. Is it private property, inherited by Habsburg descendants? Or does it count as a cultural asset that should belong to a state or to the broader public?

Because the suitcase was legally held in a Canadian bank, local authorities also have a stake in the conversation. At the same time, Austria, Italy and other successor states of the old empire follow the news closely, each with their own historical connection to the stone.

The diamond now sits at the crossroads between family inheritance law, international heritage claims and public expectation.

What might happen next

The Habsburg heirs have signalled that they do not want the jewels to vanish again into a private safe. Instead, they are reported to favour public access, at least on loan.

A first exhibition is being considered in Canada, the country that sheltered the family during its most vulnerable years. Such a show would not only present the diamond but also set it in a broader story of exile, loss and reinvention.

- Location of storage: bank safe deposit in Canada

- Period of secrecy: roughly 100 years after Emperor Karl’s death

- Key piece: pale yellow Florentine Diamond, about 137 carats

- Other items: brooches, pins, insignia set with coloured stones

- Planned future: potential public exhibition and expert evaluations

Why one gemstone matters beyond its price

On the auction market, a diamond of this size and rarity would attract staggering bids. But specialists stress that its historical weight may rival, or even exceed, its market value.

The stone is a witness to several layers of European history: Renaissance craftsmanship, baroque court life, nineteenth‑century imperial politics and the refugee experience of dethroned royals in the twentieth century.

This mix of art, politics and family drama explains why museums and governments may push for shared arrangements instead of a simple sale to the highest bidder.

How such a diamond would be handled today

If the Florentine Diamond enters museum collections or travels for exhibitions, it will be accompanied by intense security and insurance coverage. Curators would also need to balance public access with conservation rules. Strong lighting, for instance, pleases visitors but can stress ancient settings or fragile mounts.

To address those concerns, institutions often rotate high‑value gems in and out of display, limit exposure time and schedule detailed condition checks after tours. The Habsburg diamond, with its old cut and unknown repair history, would require especially careful handling.

Key concepts behind the headlines

What “carat” really means

The weight of a diamond is expressed in carats. One carat equals 0.2 grams. A typical engagement ring might hold a stone of one carat or less. The Florentine’s weight of nearly 137 carats means it would weigh over 27 grams, more like a small marble than a ring stone.

Size, though, is not everything. Colour, clarity and cut play a huge role in value. The pale yellow tone of the Florentine and its unusual double rose cut make it distinctive among famous gems.

What a rose cut says about history

Modern diamonds often feature brilliant cuts, designed to maximise sparkle under electric light. A rose cut, by contrast, comes from an earlier era of candlelit courts and salons. It has a flat base and a domed top, with triangular facets that resemble the petals of a rose.

The double rose cut on the Florentine Diamond suggests advanced skills in Renaissance or early modern workshops. It also means that any attempt to recut the stone for a contemporary look would likely erase a large part of its historical character and value.

Why hidden treasures still matter today

Stories like this one resonate far beyond aristocratic circles. Families across Europe and North America still uncover war‑era suitcases, hidden savings or letters tucked into attics. Few contain imperial diamonds, but many hold clues about migration, conflict and survival.

The Habsburg suitcase shows how an object can serve several generations at once: first as a financial back‑up, then as a protective secret, and finally as a shared reference point for public history. As debates over restitution and heritage intensify worldwide, similar cases are likely to emerge from banks and basements, each forcing a fresh look at who has the right to keep, display or sell the past.