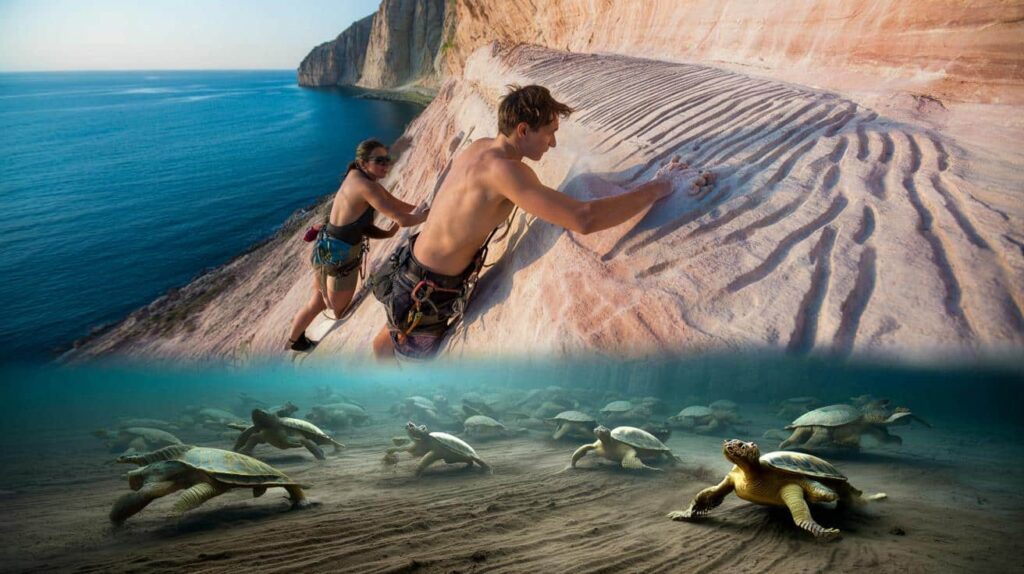

They were expecting an afternoon of bolts, chalk and coastal views. Instead, their climb on Monte Cònero, in central Italy, led them straight into the aftermath of a dramatic event that played out at the bottom of an ancient ocean nearly 80 million years ago.

A cliff face that used to be the deep sea

The story begins on the sheer rock walls of Monte Cònero, part of the Cònero Regional Park along Italy’s Adriatic coast. Today, the area draws hikers, climbers and beachgoers. During the Late Cretaceous Period, it was a deep seabed buried under hundreds of metres of water.

The cliff is made of Scaglia Rossa limestone, a famous pinkish rock unit that records millions of years of deep-sea sediment slowly piling up on the ocean floor. Tectonic forces later folded and pushed that ancient seabed upwards, transforming it into a mountain and exposing long-vanished seafloor to the open air.

As the climbers worked their way up one of these walls, they noticed something odd: long, parallel depressions cut into a single layer of limestone. They looked strikingly similar to grooves that had made headlines earlier that year elsewhere in the park, where they had been linked to a large marine reptile pushing off the seabed.

What appeared at first glance to be random scratches turned out to be the frozen traces of frantic movement on the ancient ocean floor.

Recognising they might be looking at something special, the climbers contacted fellow climber and geologist Paolo Sandroni. He, in turn, alerted Alessandro Montanari, director of the Coldigioco Geological Observatory, setting off a detailed scientific investigation.

Hundreds of tracks on a single rock layer

Sandroni and a colleague returned with a more scientific mindset and better equipment. Using ropes, they accessed the track-bearing surface, collected samples and flew a drone to photograph the cliff from multiple angles.

What they saw from above was startling: not a handful of marks, but hundreds of parallel grooves etched into the same limestone layer. The tracks formed overlapping trails that all pointed broadly in similar directions, like rush-hour traffic on a motorway that no longer exists.

Laboratory analysis of rock taken just above the track layer helped narrow down the timing and conditions. Microfossils indicated a deep marine setting, probably several hundred metres down. The age of the rock placed the event at around 79 million years ago, late in the age of dinosaurs.

The tracks sit on what was once a quiet, muddy seafloor, abruptly disturbed by a violent pulse of sediment racing downslope.

Evidence in the overlying rock shows that the track-bearing surface was quickly buried by an underwater avalanche of mud and debris, known as a submarine landslide or turbidity current. That sudden burial is what preserved the tracks so clearly.

Why sea turtle behaviour is at the heart of the mystery

Only a few types of animals living in the Late Cretaceous seas were big enough and heavy enough to carve such deep grooves into the sediment. The shortlist includes:

- Large sea turtles

- Plesiosaurs (long-necked marine reptiles)

- Mosasaurs (powerful predatory marine reptiles)

Montanari and his colleagues favour sea turtles as the likeliest track-makers. Their reasoning comes from both size and behaviour. Plesiosaurs and mosasaurs are generally thought to have been more solitary hunters. Sea turtles, by contrast, may have gathered in groups near coastlines to feed or to prepare for nesting, much like some modern species do today.

In that scenario, a cluster of turtles could have been resting or foraging near the seabed when a powerful earthquake shook the region. Startled, they would have scrambled away across the soft seafloor, kicking hard with their forelimbs, leaving repeated, parallel grooves as they tried to reach safer, deeper water or open sea.

A prehistoric stampede triggered by an earthquake

The researchers picture the event as a kind of underwater stampede. Some animals bolted upslope, others downslope. All of them were reacting to the same shock: a major quake along the ancient seafloor.

That seismic jolt likely destabilised loose sediment on the seabed. Within minutes, it would have cascaded into an underwater avalanche. This fast-moving flow, dense with mud, sand and water, swept over the tracks, buried them and locked the turtles’ frantic escape into stone.

Without the earthquake-triggered avalanche, seafloor currents and burrowing animals would have erased every trace of the ancient stampede.

Under normal conditions, tracks on the deep-sea floor do not last long. Bottom currents smear them out. Worms, clams and other “benthic” creatures constantly churn through the top layers of sediment. Geologists sometimes refer to this as “seafloor gardening”. The Italian tracks survived only because mud fell rapidly on top, sealing them off from this natural clean-up crew.

Not everyone agrees on who made the tracks

The interpretation has impressed some experts, but it has also raised questions. Michael Benton, a vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of Bristol who was not part of the study, has reservations about attributing the grooves to sea turtles.

He points out that the pattern, with both forelimbs apparently pushing down at the same time, suggests a behaviour called “underwater punting”. That is where an animal repeatedly plants its limbs into the sediment and pushes itself forward in short bursts.

Most vertebrates either walk or swim with their limbs moving out of sequence, Benton notes. Modern marine turtles tend to use a more fluid, flying-style motion with their front flippers, tracing a figure-eight pattern through the water rather than punching into the seabed.

He also raises a simple question: if a turtle felt a strong earthquake, why not just swim up off the bottom instead of shoving through the mud?

The grooves clearly record the rapid movement of large animals on the seafloor, but the exact identity of those animals remains open to debate.

Montanari agrees that further research on the detailed shape and spacing of the tracks could help resolve the issue. For now, the team is confident about the broader picture: a major quake, a sudden submarine avalanche and a cluster of marine reptiles caught in the chaos.

What an underwater avalanche actually looks like

For many people, “avalanche” brings to mind snow roaring down a mountainside. At the bottom of the sea, the physics is surprisingly similar. A submarine avalanche, or turbidity current, starts when sediment on a slope becomes unstable, often triggered by an earthquake.

Once it begins to move, the mix of grains and water behaves like a dense, fast-flowing fluid. It can race along the seafloor for tens or even hundreds of kilometres, carving channels and burying everything in its path beneath fresh layers of mud and sand.

These events pose real risks today, snapping seafloor cables and threatening offshore infrastructure. In the Cretaceous, they also created ideal conditions for fossilisation by rapidly sealing tracks, burrows and even carcasses under a protective blanket of sediment.

Key terms that help make sense of the site

| Term | Meaning at Monte Cònero |

|---|---|

| Scaglia Rossa | A limestone formation built from deep-sea mud and microscopic shells, now forming cliffs in central Italy. |

| Benthic organisms | Animals that live on or in the seabed, such as worms and clams, constantly re-working the sediment. |

| Submarine landslide | An underwater avalanche of sediment, often triggered by earthquakes, that can rapidly bury seafloor features. |

| Late Cretaceous | The final stretch of the dinosaur era, roughly 100–66 million years ago, when these tracks were made. |

Why climbers keep stumbling onto major fossils

The Monte Cònero story fits a growing pattern: climbers and outdoor enthusiasts acting as unwitting scouts for science. Vertical rock faces expose continuous slices of geological history, and climbers often spend far more time scrutinising those surfaces than most casual visitors.

Grooves that might look like random weathering to a hiker can stand out clearly to someone hanging on a rope, inspecting each hold. In this case, a chance comparison with news images of similar tracks elsewhere in the park led the climbers to seek expert advice.

For researchers, such finds offer a low-cost, high-value advantage. Instead of drilling deep-sea cores or sending expensive submersibles, they can study ancient seabeds that have conveniently been lifted into the air by plate tectonics and cleaned by natural erosion.

What this scene tells us about ancient oceans

The Monte Cònero tracks do more than supply a dramatic image of marine reptiles in panic. They also add detail to the picture of Cretaceous oceans as busy, hazard-prone places. Earthquakes regularly shook the seafloor. Sediment cascades reset local habitats in minutes. Animals that seemed perfectly adapted to their environment still faced sudden, life-threatening shocks.

For modern readers, there are parallels with present-day concerns. Submarine landslides can still be triggered by quakes, volcanic eruptions or even the rapid build-up of sediment from rivers. As sea levels rise and human activity spreads offshore, understanding how often such events occur, and how far they travel, matters for coastal planning and infrastructure.

The Italian “stampede” snapshot, sealed inside pink limestone, shows how a single seismic event can leave a signature that endures for tens of millions of years. It also highlights how everyday activities—like climbing a local route—can intersect with deep time, revealing moments when ancient animals, startled and confused, reacted in ways that feel surprisingly familiar.